Introduction

A basic group in the

security, food sovereignty and cultural identity of the Andean countries is the

one made up of tubers, among which are “ibias” or “ocas” (Oxalis tuberosa Molina),

“cubios”, “nabos” or “majuas” (Tropaeolum tuberosum Ruiz & Pav.),

“chuguas” or “ullucos” (Ullucus tuberosus Caldas) and potatoes (Solanum

tuberosum L.), all with a wide diversity in the inter-Andean valleys

(Clavijo-P. et al., 2014; García et al., 2018; Viteri et al., 2020).

Oxalis tuberosa has been used by Andean populations for thousands of years, it

has an adaptation to environments where other crops cannot survive, including

tolerance to cold climates, thrives in soils with pH of 5.3 to 7.8, resistant

to various pests and other phytosanitary problems (Rosero, 2010; Clavijo-P. &

Pérez-M., 2014).It is probable that this species or some related ones, have

been consumed and perhaps cultivated by the inhabitants of the inter-Andean

valleys since the Holocene (Clavijo-P. et al., 2014). Rosero-A. (2010)

identified the south of the department of Nariño, especially the municipalities

of Cumbal, Guachavéz, El Encano and Puerres, as the area of greatest diversity

of this species in the department. Although the species is a material that propagates vegetatively

cycle after cycle, there is evidence of variation at the phenotypic and

genotypic level that should be conserved and used for the generation of new and

better materials that respond to the interests of farmers, producers and

consumers (Morillo et al., 2016; Clavijo-P. y Pérez-M., 2014), but conserving

native germplasm to avoid its loss.

The Tropaeolum tuberosum,

like O. tuberosa thrives in cold climates and is tolerant of various

types of pests and diseases, but its taste is not very liked by the population

due to its strong bitter taste caused by the high content of isothiocyanates

derived from glucosinolates (Grau et al., 2000) which has decreased its

consumption, despite presenting high nutritional and very possibly medicinal

value (Leidi et al., 2018). Two possible domestication centers are proposed for

this species, the highlands located between Peru and Bolivia and the Cundiboyacense

savanna in Colombia, where varieties with dissimilar morphological and

physiological characteristics are found (Grau et al., 2003; Tapia &

Fries,2007). However, Seminario (2004), considers that the tuberization

phenomenon is related to adaptations to areas with prolonged periods of

drought, rare phenomena in the Colombian region. Manrique et al. (2014) identified the micro-centers of

diversity by morphological characterization of 107 accessions; finding that the

states of Huancavelica, Junín, Pasco and Cusco represent 62% of all Peruvian

accessions (Manrique et al., 2014). In the state of Cusco, Ortega et al.

(2007), analyzed the patterns of genetic diversity of cultivated and wild

populations of T. tuberosum, a wide genetic diversity was found, and it

was determined that wild populations are closely related to cultivated ones.

These results strengthen the Cusco region as a micro center of diversity of T.

tuberosum.

Ullucus tuberosus

and T. tuberosum have been shown

to have more than 35% starch, along with high resistance to pests, low

temperatures and drought (Campos et al., 2018; Naranjo et al., 2017). Tapia &

Fries (2007) consider that one of the domestication centers of U. tuberosus is

Colombia, since the cultivated morphotypes present wild characteristics such as

creeping growth and smaller diameter of the tubers. However, Parra-Q et al.

(2012) suggest that the site of origin was in the central Andes, between Peru

and Bolivia, from where it was dispersed semi-domesticated towards Colombia and

later the erect growth morphotypes were domesticated that had a new wave of

dispersal towards the north. In Colombia, in the departments of Boyacá and

Cundinamarca, 36 accessions were morphologically and molecularly characterized

and it was concluded that the populations of the center of the country

correspond to the subspecies in the process of domestication, given its decumbent

growth and its genetic distance with the populations of the south of the

country (Parra-Q. et al., 2012).

Regarding potatoes, it is

widely accepted that one of the main centers of initial domestication of

potatoes is in southern Peru on the border with Bolivia 10,000 years ago

(Hawkes & Ruel, 1989). From the domesticated species and through

hybridization with other species of the genus, the other species of the section

would have been obtained Petota. Another center for domestication of

potatoes is the island of Chiloé in Chile, where wild and domesticated species

of Solanum have been recorded (Tapia & Fries 2007; Ovchinnikova et

al., 2011, Cadima & Terrazas, 2019). According to Gómez et al.

(2012), Colombia is the center of origin and domestication of Creole potatoes, S.

phureja. Navarro et al. (2010) morphologically and molecularly

characterized 19 genotypes of S. tuberosum and S. phureja in

Nariño, Colombia; however, it was found that neither morphological nor

molecular markers can clearly distinguish the evaluated species and varieties.

In fact, Huamán & Spooner (2002) morphologically characterized eight

species of potatoes in Latin America and concluded that given the genetic

plasticity and continuous hybridization, all the evaluated potatoes could well

be classified as a single species, S. tuberosum, with eight different

cultivars.

As can be seen, the high

varietal and intravarietal diversity of these species has been promoted and

accumulated after thousands of years of selection and management by traditional

Andean farmers. However, factors such as the homogenization of agroecosystems,

cultural uprooting and the globalization of the diet, endanger the future

maintenance of this diversity (Malice & Baudoin, 2009); in the nineties

Stephen Brush (Brush et al, 1992), and those of Karl Zimmerer, carried out

several studies where they identified the factors that led to the incorporation

of new varieties, but they also highlighted that some groups of peasants sought

the conservation of native species, almost thirty years later Velásquez-M et al.

(2016). They also point out the need to apply various actions for conservation,

including the identification of agrobiodiversity zones at the local, regional

and national level, to avoid genetic erosion.

The distribution of the

diversity of Andean tubers is not homogeneous but is identified concentrated in

micro-centers of diversity and outside of them less interspecific diversity is

conserved: various authors have identified as micro centers of diversification

of these: Cajamarca, Huancavelica, Huánuco and Cusco in Perú; in Bolivia the

Altiplano and La Candelaria territories; in Ecuador the provinces of Carchi and

Huaconas and in Colombia in the departments of Boyacá and Nariño (García &

Cadima, 2003; Seminario, 2004; Ortega et al., 2007; Parra-Q. et al. 2012;

Manrique et al. 2014, Clavijo-P. et al. 2014; Fonseca et al., 2014). These

micro-centers of diversification share a high intravarietal diversity, both

morphological and genetic, as well as an important cultural roots of these

species. The latter is possibly due in part to the fact that they occupy the

same agroecological niche and the farmer generally sows them in association or

in very close plots with similar management (Tapia, 2000).

Panbiogeography is a

geographic approach applied to contribute to the understanding of biodiversity

by identifying biotic components, individual traces, generalized traces and

panbiogeographic nodes, starting from the distribution of plant and animal

species (Morrone, 2004), which was proposed by Leon Croizant in 1952. Based on

the coordinates of the presence of a certain taxon, lines are constructed that

connect all the points so that the sum of the segments is the smallest possible

(individual trace or minimal laying tree); generalized traces result from the

superposition of individual traces of a phylogenetically related group;

panbiogeographic nodes are defined as the nodes of the generalized lines and

can be interpreted as areas where there is a greater presence of endemisms,

greater phylogenetic diversity and geographic limits of taxa (Miguel-T

& Escalante, 2013).

These methods have been used

to analyze the distribution of wild species (Martínez-G. & Morrone, 2005;

Arana et al.,2013; Morrone, 2013), but they have not been used to understand

the distribution of cultivated species, considering that the distribution

patterns of cultivated plants are not only governed by natural evolutionary

dynamics but especially by anthropic dynamics.

The objective of this study is to identify for the tuberous species of the

Andes, the agrogeographic nodes, thus named to the points that imply the

intersection of sociocultural and biogeographic histories, which can have the

following interpretations: presence of unique local cultivars, absence of

widely distributed varieties, high inter- and infra-specific diversity and agro-ecosystemic

affinities between areas. To compare the microcenter nodes reported in the

bibliography with the agro-geographic nodes, the generalized line resulting

from intersecting the individual lines of the Andean tubers will be estimated (S.

tuberosum, O. tuberosa, U. tuberosus and T. tuberosum). In

this way it will be possible to identify potential areas of concentration of

the diversity of Andean tubers not previously reported. The identification of

these areas will guide research on the conservation and management of Andean

tubers. In addition, the agro-geographic nodes shed elements of discussion on

the exchange of seeds and knowledges between indigenous peoples.

Materials

and Methods

A database was built of the

distribution of O. tuberosa, U. tuberosus, T. tuberosum and

S. tuberosum in: Chile, Argentina, Bolivia, Perú, Ecuador, Colombia, and

Venezuela, from the records integrated into the global geographic information

platform, Global Biodiversity Information Facility (Global Biodiversity

Information Facility [GBIF], 2017). Individuals which presented coordinates of

complete geographic distribution, latitude, longitude, state and municipality

were taken into account.

According to panbiogeographic

theory, the distribution coordinates of each species were individually

connected in such a way that the distance between the points was minimal,

taking into account the curvature of the Earth (Miguel-T. & Escalante,

2013). This procedure was performed with the program PASSaGE 2.14.3 ‘Essen’

(Rosenber & Anderson, 2011) and Quantum-GIS 2. (Sherman et al., 2007),

applying the combined method (Liria, 2008), which combines spatial analysis

through geodetic distance calculation, creating a connectivity matrix and

minimum spanning trees, with layer management and GIS spatial operations of

intermediate storage and interception, thus the individual traces obtained from

each species intersect each other to obtain the generalized traces and the agro-geographic

nodes.

Analogously to the main biogeographic nodes

(Morrone, 2015a), the main agro-geographic nodes correspond to the areas where

there are more points of intersection of the analyzed species and the secondary

ones also represent important areas of diversity but of lesser magnitude. The

main nodes, in terms of wild species, identify the areas where speciation

phenomena possibly occurred; while for cultivated species they would indicate

initial domestication phenomena, from where they would distribute the seeds to

other areas where they would continue their domestication.

Results

A number of 8975 records had

the required geographic information. The species with the highest abundance is S.

tuberosum with 6056 records distributed in Peru (3088), Argentina (943),

Bolivia (783), Colombia (502), Ecuador (410), Chile (294) and Venezuela (36);

regarding infraspecific taxa, it was found that the subspecies S. tuberosum

andigena (Juz. & Bukasov) Hawkes y Roel

(2006) cuenta con mayor número de registros (3758), Solanum

stenotomum Juz. & Bukasov (456), Solanum phureja Juz. &

Bukasov (359), Solanum chaucha Juz. & Bukasov (352) y los registros

restantes corresponden a otras variedades y formas de S. tuberosum L (GBIF,

c2017).

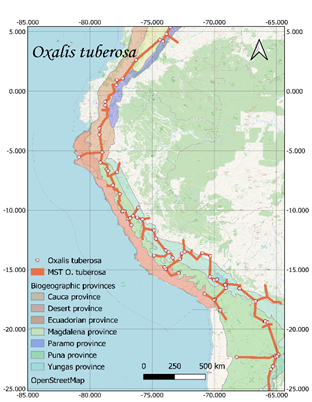

For its part, O. tuberosa

had 1400 records distributed in Peru (1056), Bolivia (146), Argentina (111),

Ecuador (63), Chile (13) and Colombia (11) (GBIF, c2017).

U. tuberosus presented 1010 records; 736 in Peru, 137 in Ecuador, 83 in

Bolivia, 38 in Argentina and 16 in Colombia (GBIF, 2017).

Table 1. Accessions of species in relation to their geographical origin.

|

Perú

|

Argentina

|

Bolivia

|

Colombia

|

Ecuador

|

Chile

|

Venezuela

|

Total

|

|

S. tuberosum

|

3088

|

943

|

783

|

502

|

410

|

294

|

36

|

6056

|

|

O. tuberosa

|

1056

|

111

|

146

|

11

|

63

|

13

|

|

1400

|

|

U. tuberosus

|

736

|

38

|

83

|

16

|

137

|

|

|

1010

|

|

T. tuberosum

|

350

|

6

|

29

|

24

|

100

|

|

|

509

|

|

Totales

|

5230

|

1098

|

1041

|

553

|

710

|

307

|

36

|

8975

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

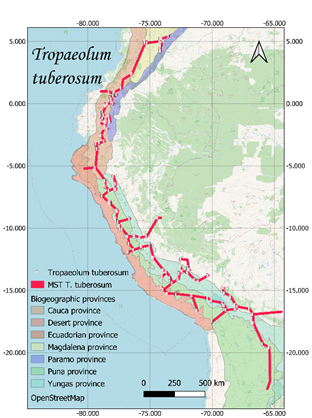

Finally, T. tuberosum was

registered 509 times, 40 of them correspond to T. tuberosum silvestre

Sparre and the remaining 469 to T. tuberosum Ruiz & Pav.; Regarding

the distribution by countries, Peru reports 350, Ecuador 100, Bolivia 29,

Colombia 24 and Argentina six (Global Biodiversity Information Facility [GBIF],

2017).

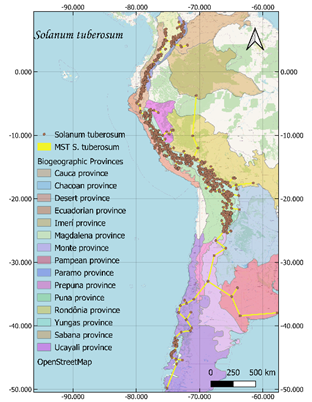

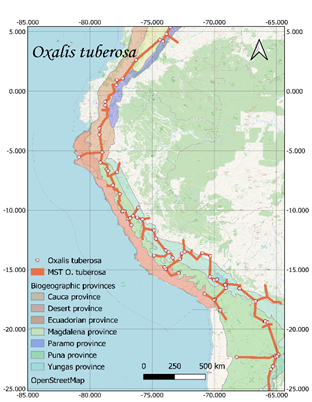

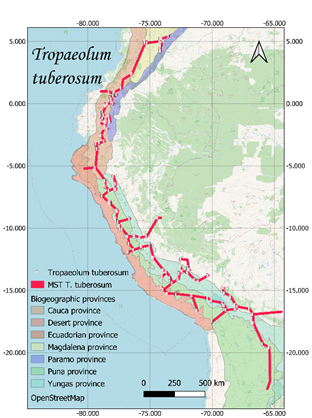

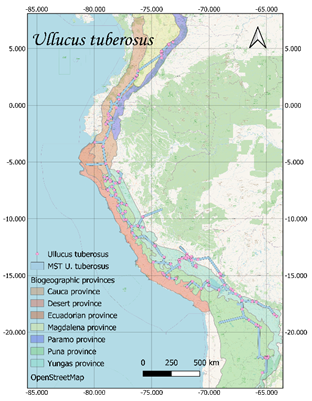

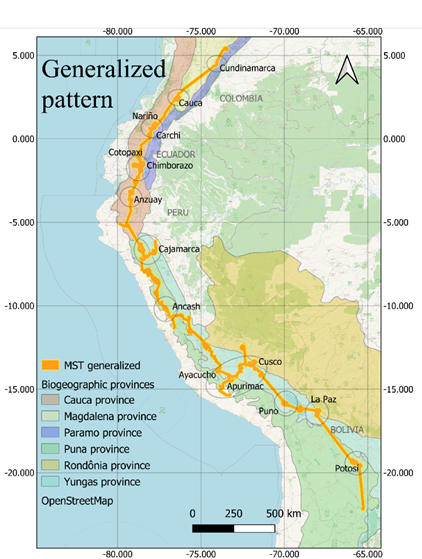

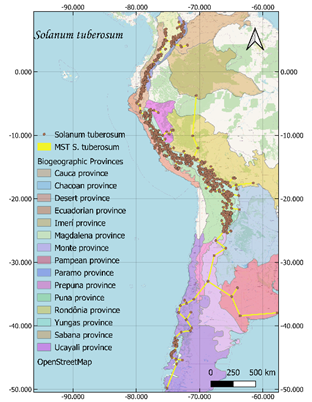

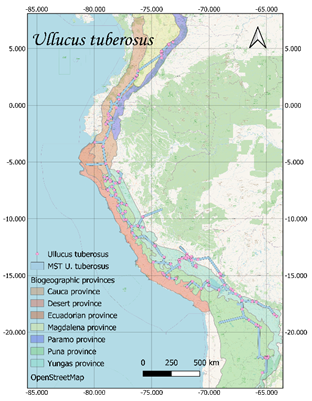

Andean tubers are distributed

in the biogeographic regions of the Transition Zone of South America, provinces

of Páramo, Puna, Desierto, Monte, Maule, Santiago and Valdivia, and from the

Neotropical region in the provinces of Yungas, Rodonia, Ucayali, Cauca,

Ecuatorian, Western ecuadorian, Magdalena, Sabana and Chaco. The provinces with

the highest number of records are Yungas for S. tuberosum with 2241, while in

the province of Puno the highest number of records is reported for U.

tuberosus (453), O. tuberosa (805) and T. tuberosum (166);

the western Ecuadorian and Sabana provinces are the ones with the fewest

records with a single report for T. tuberosum and O. tuberosa,

respectively (Figure 1).

Current distribution maps and

individual traces of each of the species were obtained (Figure 1). These lines

converge in a generalized line that runs from the north of Argentina to the

center of Colombia, crossing through Bolivia, Peru and Ecuador.

Figure 1. Distribution and minimum laying tree of S. tuberosum, O.

tuberosa, U. tuberosus and T. tuberosum on biogeographic provinces

(Loöwenberg-Neto, 2014) and Open Street Map.

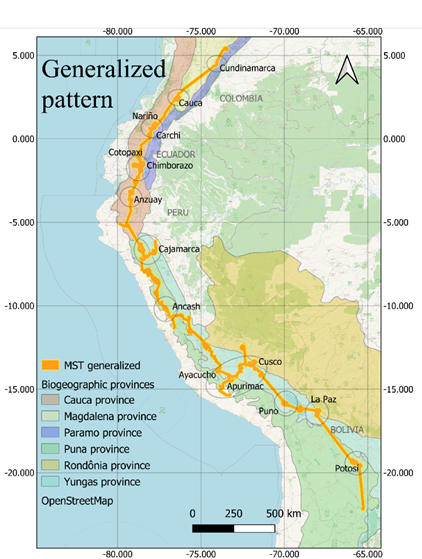

The main node of this trace,

or primary agro-geographic node occurs in southern Peru, a secondary node was

identified in the north of this country and several secondary nodes were found

in Bolivia, in central Peru, in central Ecuador and on the borders between

Colombia and Ecuador (Figure 2). Regarding the biogeographic

distribution, the number of nodes is greater in the southern Brazilian domain,

followed by the South American Transition Zone and the Pacific domain.

Figure 2.

Generalized trace and agrogeographic nodes (in circles) of Andean tubers on

Biogeographic Provinces (Löwenberg -Neto, 2014). and Open Street

Map.

In Peru, 1,245 of the 2,043 generalized or intersection

coordinates were identified (61%). The main node is between the departments of

Cusco (277), Apurímac (111) and Ayacucho (89) and in second order are the nodes

of Cajamarca (181), Ancash (134) and Puno (103) that stand out for the number

of intersection points of individual traces.

In Ecuador, 459 sites with

intersection coordinates (22.5%) were found, located mainly in the provinces of

Chimborazo (123), Cotopaxi (61), Carchi (51) and Anzuay (42).

In Bolivia there were 204

sites with intersection coordinates (10%), identified in the departments of La

Paz (109) and Potosí (95); the municipalities of Tomás Frías (83) Pedro Domingo

Murillo (39) and Manco Kapac (34) were the ones that presented the highest

abundance of intersection coordinates in the country.

In Colombia, 131 sites with intersection

coordinates (6.5%) were identified, in the departments of Cauca (46), Nariño

(37), Cundinamarca (28) and Boyacá (19), mainly. In Nariño, the municipalities

of Cumbal (16) and Ipiales (6) were the most representative; in Cauca they were

Totoró (18) and Silvia (11); in Cundinamarca the municipalities with the

highest abundance are Chipaque (11), Bogotá (5), Pasca (5) and Ubaque (4);

Finally, in Boyacá, the municipality of Samacá (12) was the one that presented

the highest abundance.

Discussion

According to biogeographic

theory, panbiogeographic nodes imply the intersection of different ecological

and biogeographic histories that can have the following interpretations:

presence of local endemisms, absence of widely distributed taxa, high

phylogenetic diversity and geographic affinities with other areas and

boundaries or geographic or phylogenetic of taxa (Miguel-T & Escalante,

2013; Morrone, 2015b; Grehan, 2020). In this analysis, the identified nodes do

not correspond to panbiogeographic nodes but to agro-geographic nodes,

understanding that human beings have been decisive in the flow of seeds of

cultivated plants, as well as in the selection and adaptation of their

varieties (Velásquez et al., 2013).

Molecular studies confirm the

highlands of Peru, departments of Huánuco, Pasco, Junín, Huancavelica,

Apurímac, Ayacucho, Cusco and Puno as the domestication region of S. tuberosum;

where, due to temperature fluctuations, the development of plants with growth

of underground propagules is favored (Morales-G., 2007). The first presence of

potatoes in Peru dates back to 6900 years ago in the department of Lima and

towards the beginning of the Formative period (3,800 years ago) in the

department of Junín (Morales-G, 2007). Spooner et al. (2005) suggest that the

domesticated potato comes from the wild species of the S. brevicaule

complex from southern Peru, although this complex extends from Huánuco to Puno.

Currently in the region of Cusco, Apurímac and Huancavelica it is common to

find conservationist farmers for whom biodiversity is their lifestyle and

therefore they grow 50, 100 or 300 varieties of potatoes in plots smaller than

one hectare (Fonseca et al., 2014).

The Cusco region is also an

important area for the conservation of the other Andean tubers. T. tuberosum

registers a greater genetic and morphological diversity in the agroecosystems

of this area than that conserved in the collection of the International Potato

Center (Manrique et al., 2014). O. tuberosa it also presents a high

diversity in the departments described, as well as in Cajamarca, Ancash and

Puno (Pissard et al., 2008). Currently, the exchange between Andean tuber seed

farmers has been reported between the Peruvian departments of Huánuco,

Huancayo, Huancavelica, Ayacucho, Cajamarca and Cusco (Velásquez et al., 2013).

In Bolivia, the departments

of La Paz and Cochabamba have been reported as micro-centers of diversity of

Andean tubers in this country (García & Cadima 2003). Cochabamba is one of

the regions with the greatest morphological and molecular diversity of O.

tuberosa (Emshwiller & Doyle, 1998), T. tuberosum (Grau et al.,

2003) and U. tuberosus (Parra-Q., 2012).

The Ecuadorian departments of

Carchi, Cañar, Bolívar, Chimborazo, Cañar, and Loja, present a wide diversity

of potatoes (Morales-G 2007), ullucos (Vimos et al., 1993) and Mashuas (Grau et

al., 2003). In Colombia, the use of lithic tools has been reported for more

than 5000 years as hoes, the edges of which have residues of starch from tubers

(Aceituno-B & Rojas-M, 2012). The southeastern part of the country, mainly

the municipality of Cumbal and others in the department of Nariño, are

recognized micro-centers of potato diversity (Tinjacá-R. & Rodríguez-M.,

2015) and ullucos (Parra-Q., 2012). In the department of Boyacá, the

municipality of Ventaquemada has been identified (Clavijo-P. et al., 2014) as

one of the Colombian micro-centers. However, in our analysis the municipality

of Samacá was also identified as the administrative unit where the intersection

coordinates in the department concur with greater abundance. The department of

Cauca was also identified, especially the municipalities of Totoro and Silvia,

as those with the greatest presence of coordinates where the four species are

present in the department; however, studies have not yet been carried out to

determine the varietal diversity of these resources. The same occurs in the

department of Cundinamarca, where the municipality of Chipaque has the highest

abundance of intersection coordinates but does not have associated studies.

Biological diversity is

concomitant to areas where there is also a high cultural diversity as a whole,

they make up biocultural diversity, a key diversity in the processes of plant

domestication in Mesoamerica and the Andes (Casas et al., 2017). In this sense,

the identified nodes concur in areas of indigenous predominance: Quechua

(Bolivia, Peru, Ecuador, and Colombia), Aimara (Peru and Bolivia), Pastos

(Ecuador and Colombia), Nasa, Misak and Coconucos (Colombia); With the

exception of the node in central Colombia where only remnants of the Muisca

indigenous group remain (Albo et al., 2009).

The panbiographic analysis of Andean tubers offers two benefits,

namely: First, it allows the identification of the geographic areas with the

greatest agrobiodiversity and this in turn is important to direct protection

and recovery strategies for plant genetic resources. On the other hand, it also provides evidence in the

reconstruction of the history and diffusion of domestication in America,

allowing temporal trans-scalarity, that is, connecting the interpretation of

past events with current processes (Casas et al., 2017). The results support

the hypothesis that Andean tubers were domesticated in the Peruvian highlands,

from where they dispersed to the south and north following the patterns of

pre-Columbian human occupations. In this sense, the history of the Andean tubers

can be understood as the history and future of the Andean peoples (Viteri et

al., 2020; Devaux et al., 2021; Montes et al., 2021).

Author

contributions

Conceptualization: R.F.G.-D, E.F.V.-H,

L.M.-C. Experiment design: R.F.G.-D, E.F.V.-H., L.M.-C.,

F.J.D.-N., S.A.-S. Experiment execution: R.F.G.-D, E.F.V.-H. Experiment

verification: R.F.G.-D, E.F.V.-H.,

L.M.-C., F.J.D.-N., S.A.-S. Data

analysis/interpretation: R.F.G.-D., E.F.V.-H., L.M.-C., F.J.D.N.,

S.A.-S. Statistical analysis: R.F.G.-D, E.F.V.-H., L.M.-C., F.J.D.N.,

S.A.-S. Manuscript preparation: R.F.G.-D,

E.F.V.-H., L.M.-C., F.J.D.-N., S.A.-S. Manuscript editing and revision: R.F.G.-D, E.F.V.-H., L.M.-C.,

F.J.D.-N., S.A.-S. Approval of the final

manuscript version: R.F.G.-D, E.F.V.-H., L.M.-C., F.J.D.-N.,

S.A.-S.

Financing

This study was supported by the “Corporación

Universitaria Minuto de Dios (Dirección General de Investigaciones y Centro

Regional Zipaquirá)” by funding this research within the framework of the

project C116-085 "Andean tubers back home: participatory conservation of

tuberous species in Cundinamarca".

References

Aceituno-B. F. &

Rojas-M. S. (2012). Del peleoindio al formativo: 10000 años para la historia

lítica en Colombia. Bol. Antropol., 26(43), 124-156.

Albo, X., Argüelles, N., Ávila,, R., Bonilla, L. A., Bulkan, J.,

Callou, D., Carriazo, C., De Castro, A. F., Censabella, M., Crevels, M., Díaz,

M., Couder, E. D., García, F., Haboud, M., Hernández, A., Leite, Y., Koskinen.,

A., Lemus, J., López, L. E., … & Trillos, M. (2009). Atlas

sociolingüístico de pueblos indígenas en américa latina. Bolivia. [UNICEF]

Fondo de las Naciones Unidas para la Infancia, [FUNPROEIB] Fundación para la

Educación en Contextos de Multilingüismo y Pluriculturalidad, Andes. 522 p.

Arana, M., Ponce, M., Morrone, J. &

Oggero. A. (2013). Patrones biogeográficos de los helechos de las sierras de córdoba

(Argentina) y sus implicancias en la conservación. Guayana

Bot., 70(2), 357-376.

Brush, B. S., Taylor, J. E. &

Bellón, M. R. (1992). Technology adoption and biological diversity in andean

potato agriculture. J. Dev. Econ., 39(2), 365-387.

Cadima X. & Terrazas, F. (2019). Caracterización de los

semilleristas tradicionales de papa en Bolivia. Revista Latinoamericana de

la Papa, 23(1), 56 – 62

Campos, D., Chirinos, R.,

Gálvez-Ranilla, L. & Pedreschi, R. (2018). Bioactive

potential of andean fruits, seeds, and tubers. Advances in food and

nutrition research, 84, 287-343.

Casas, A., Parra, F., Torres-G., I., Rangel-L., S., Zarazúa M.

& Torres-G J. (2017). Estudios y patrones continentales de domesticación y

manejo de recursos genéticos: perspectivas. En:Casas, A., Torres-G., J. &

Parra-R. editores. Domesticación en el continente americano. México.

Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México, Universidad Nacional Agraria la Molina

del Perú. 538-563.

Clavijo-P., N. L. & Pérez-M.

M. E. (2014). Tubérculos andinos y conocimiento agrícola local en comunidades

rurales Ecuador y Colombia. Cuadernos de desarrollo rural, 11(74),

149-166. doi:10.11144/Javeriana.CRD11-74.taca.

Clavijo-P., N. L., Barón, M. T.

& Combariza, J. A. (2014). Tubérculos andinos: conservación y

uso desde una perspectiva agroecológica. Bogota.

Pontificia Universidad Javeriana.

Devaux, A., Hareau G., Ordinla,

M., Andrade-Piedra, J. & Thiele G. (2021). Las papas nativas: de ser un

cultivo olvidado al boom culinario e innovación de mercado. Revista

Latinoamericana de la Papa, 25 (2), 3–14. doi: 10.37066/ralap.v25i2.429.

Emshwiller, E. & Doyle, J. (1998). Origins of

domestication and polyploidy in oca (Oxalis tuberosa: oxalidaceae):

nrdna its data. Am J Bot., 85(7), 975–985.

doi:10.2307/2446364.

Fonseca, C., Rodríguez, F., Munoa, L. & Ordinola M. (2014).

Catálogo de variedades de papa nativa con potencial para la seguridad

alimentaria y nutricional de apurímac y huancavelica. Perú. Centro

Internacional de la Papa. doi:10.4160/9789290604549.

García, R. F., Jiménez, L., Bernal P. S., Robayo, O., Chaparro, M.

D., Sierra F. M., Camacho, P.A., Vanegas, J., Rincón, J. S. & León-S, T. E.

(2018). Tubérculos andinos de vuelta a casa: conservación participativa de

tubérculos andinos en cundinamarca. Bogotá D.C., Corporación Universitaria

Minuto de Dios.

García, W. & Cadima, X., editores. (2003). Manejo

sostenible de la agrobiodiversidad de tubérculos andinos: síntesis de

investigaciones y experiencias en bolivia. Conservación y uso de la

biodiversidad de raíces y tubérculos andinas: Una década de investigación para

el desarrollo (1993-2003). Bolivia. Fundación para la Promoción y la

Investigación de Productos Andinos PROINPA, Alcaldía de Colomi, Centro

Internacional de la Papa ClP, Agencia Suiza para el Desarrollo y la Cooperación

COSUDE.

Global Biodiversity Information

Facility [GBIF]. (2017). http://www.gbif.org

Gómez-P., T. M., López-O, J. B., Pineda-T., R., Galindo-L., L. F.,

Arango-I. R. & Morales-O, J. G. (2012). Caracterización citogenética de

cinco genotipos de papa criolla, Solanum phureja (juz. Et buk.). Rev.

Fac. Nac. Agron. Medellín., 65(1), 6379–6387.

Grau, A., Ortega-D., R., Nieto-C., C. & Hermann M. (2003). Mashua

Tropaeolum tuberosum Ruiz and Pav. Promoting the conservation and use of

underutilized and neglected crops. 25. Italy. International Potato Center,

Lima, Perú/ International Plant Genetic Resources Institute.

Grau, A., Ortega, R., Nieto, C. & Hermann, M. (2000). Promoting

the conservation and use of underutilized and neglected crops. Mashua

(Tropaeolum tuberosum Ruiz and Pav,). Rome,

Italy. IPGRI, 54p.

Grehan, J. (2020). Conserving

biodiversity as well as species. BSO Newsletter 80, 14-18

Hawkes, C. & Ruel, M. T.

(2006). Understanding the links between agriculture and health. Washington:

International Food Policy Research Institute.

Hawkes, J. G. (1989). The

domestication of roots and tubers in the american tropics. In Harris, D.R.,

Hillman, G.C., editors. Foraging and farming. The evolution of plant

exploitation. Unwin Hyman, London, 481-503.

Huamán, Z. & Spooner, D. M.

(2002). Reclassification of landrace populations of cultivated potatoes (Solanum

sect. Petota). Am J Bot. 89(6),947–965. doi:10.3732/ajb.89.6.947.

Leidi E.O, Monteros-Altamirano,

A., Mercado, G., Rodríguez, J. P., Ramos, A., Alandia, G., Sorenses, M. &

Jacobsen, S.E. (2018). Andean roots and tubers crops as

sources of functional foods. J. Funct. Foods., (51),

86-93. doi: 10.1016/j.jff.2018.10.007.

Liria J (2008). Sistemas de

información geográfica y análisis espaciales: un método combinado para realizar

estudios panbiogeográficos. Revista Mexicana de Biodiversidad 79: 281-

284.

Löwenberg-Neto, P. (2014). Neotropical region: a shapefile of Morrone's

(2014) biogeographical regionalisation.

Zootaxa,

3802 (2), 300-300

Malice, M. & Baudoin, J.P. (2009).

Genetic diversity and germplasm conservation of three minor andean tuber crop

species. Biotechnol Agron Soc Environ., 13(3),

441–448.

Manrique, I., Arbizu, C., Vivanco, F., Gonzales, R., Ramírez, C.,

Chávez, O., Tay, D. & Ellis, D. (2014). Tropaeolum

tuberosum Ruíz & Pav. Colección de germoplasma de mashua conservada en

el Centro Internacional de la Papa (CIP). Lima.

CIP. doi:10.4160/9789290604310.

Martínez-G. M. & Morrone, J. (2005). Patrones de endemismo y

disyunción de los géneros de euphorbiaceae sensu lato: un análisis

panbiogeográfico. Bol. Soc. bot. Méx., 77, 21-23.

Miguel-T., C. & Escalante, T. (2013). Los nodos: el aporte de

la panbiogeografía al aporte de la biodiversidad. Biogeografía, 6,

30-42.

Montes, J. M., Daza, L. F. &

Angarita, L. M. (2021). Productos andinos para el desarrollo de una gastronomía

nacional. Sosquua, 2(2), 59-69.

Morales G., F. J. (2007).

Sociedades precolombinas asociadas a la domesticación de la papa Solanum

tuberosum en Sudamérica. Revista Latinoamericana de la Papa, 14(1),

1-9.

Morillo, C.A., Morillo, C. Y.

& Tovar, L.Y. (2016). Caracterización molecular de cubios (Tropaeolum

tuberosum Ruíz y Pavón) en el departamento de Boyacá. Rev

.Cienc. Agric., 33(2), 32–42.

doi:10.22267/rcia.163302.50.

Morrone J. (2015b). Track analysis

beyond panbiogeography. J. of Biogeogr, 42, 413-425.

Morrone, J. (2004). Panbiogeografía,

componentes bióticos y zonas de transición. Rev. Bras.

Entomol., 48(2), 149-162.

doi:10.1590/S0085-56262004000200001.

Morrone, J. (2015a).

Biogeographical regionalisation of the andean region. Zootaxa, 3936(2),

207-236. doi:10.11646/zootaxa.3936.2.3.

Morrone, J. J. (2013). Cladistic

biogeography of the Neotropical region: identifying the main events in the

diversification of the terrestrial biota. Cladistics: 1-13. http://10.1111/cla.12039

Naranjo Quinalusa, E. J., Tapia

Bastidas, C. G., Velázques Feria, R. J., Cruz Péres, Y., Delgado Pilla, A. H.,

Borja Borja, E. J. & Paredes Andrade, N. J. (2017). Caracterización

eco-geográfica de melloco (Ullucus tuberosus) En la región alto andina

del ecuador. Revista agro ciencias, (19)

Navarro, C., Bolaños, L. C. y

Lagos, T. C. (2010). Caracterización morfoagronómica y molecular de 19

genotipos de papa guata y chaucha Solanum tuberosum L. y Solanum

phureja Juz et Buk cultivados en el Departamento de Nariño. Revista de

Agronomía. 27 1 27–39.

Ortega, O. R., Duran, E., Arbizu,

C., Ortega, R., Roca, W., Potter, D. & Quiros, C. (2007). Pattern

of genetic diversity of cultivated and non-cultivated mashua, Tropaeolum

tuberosum, in the Cusco region of Perú. Genet Resour Crop Evol. 54(4),

807–821. doi:10.1007/s10722-006-9160-y.

Ovchinnikova, A., Krylova, E.,

Gavrilenko, T., Smekalova, T., Zhuk, M., Knapp, S. & Spooner, D. M. (2011).

Taxonomy of cultivated potatoes (Solanum section petota: solanaceae).

Biol. J Linnean. Soc., 165(2):107–155. doi:10.1111/j.1095-8339.2010.01107.x

Parra-Q., M., Panda, S, Rodríguez,

N. & Torres, E. (2012). Diversity of uUlucus tuberosus

(basellaceae) in the colombian andes and notes on ulluco domestication based on

morphological and molecular data. Genet Resour Crop Evol., 59(1), 49–66.

doi:10.1007/s10722-011-9667-8.

Pissard, A., Arbizu, C., Ghislain,

M., Faux, A. M., Paulet, S. & Bertin, P. (2008). Congruence between

morphological and molecular markers inferred from the analysis of the

intra-morphotype genetic diversity and the spatial structure of Oxalis

tuberosa mol. Genética, 132(1):71–85. doi:10.1007/s10709-007-9150-9.

Rosenberg, M.S. & Anderson, C.

D. (2011). Passage: pattern analysis, spatial statistics and geographic

exegesis. Version 2. Methods in Ecology and Evolution, 2(3), 229-232.

Rosero-A., M. G. (2010). Colección,

caracterización y conservación de variabilidad genética de oca (oxalis tuberosa

mol) en agroecosistemas paramunos del departamento de nariño-colombia. (Tesis

Maestría). Palmira. Universidad Nacional de Colombia.

Seminario J. (2004). Origen de

las raíces andinas. En Seminario J., editor. Raíces Andinas: Contribuciones

al conocimiento y a la capacitación. Serie: Conservación y uso de la

biodiversidad de raíces y tubérculos andinos: Una década de investigación para

el desarrollo (1993-2003) Nº 6. Lima. Universidad Nacional

de Cajamarca, Centro Internacional de la Papa y Agencia Suiza para el

Desarrollo y la Cooperación.

Sherman, G. E.; Sutton, Blazek,

R.; Holl, S.; Dassau, O.; Mitchell, T.; Morely, B. & Luthman, L.. (2007).

Quantum GIS ver.0.8 ‘TITAN’.

Spooner, D. M., McLean, K.,

Ramsay, G., Waugh, R., Bryan, G.J. (2005). A single domestication for potato

based on a multilocus amplified fragment length polymorphism genotyping. Proc Natl

Acad Sci U S A, 102,14694-14699. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0507400102.

Tapia M.E. 2000. Cultivos andinos

subexplotados y su aporte a la alimentación (Versión 1.0) Santiago de Chile. FAO.

http://www.fao.org/tempref/GI/Reserved/FTP_FaoRlc/old/prior/segalim/prodalim/prodveg/cdrom/contenido/libro10/home10.htm

Tapia, M. E. (1997). Cultivos

andinos subexplotados y su aporte a la alimentación (Version 1.0). Santiago de

Chile. FAO. https://bibliotecadigital.infor.cl/handle/20.500.12220/3020

Tapia, M. E. & Fries, A. M. (2007). Guía de campo de los

cultivos andinos. Lima: FAO y ANPE.

Tinjacá-R., S. & Rodríguez-M., L. E. (2015). Catálogo de

papas nativas de nariño, Colombia. Bogotá: Universidad Nacional de

Colombia.

Velásquez-M., D., Casas, A., Torres-G., J. & Cruz-S., A.

(2016). Erosión genética de las comunidades andinas. En Casas A., Torres-G., J.

& Parra, F., editores. Domesticación en el continente americano. 1, 97-131.

Velásquez, D., Trillo, C., Cruz, A. & Bueno S. (2013).

Intercambio tradicional de semillas de tuberosas nativas andinas y su

influencia sobre la diversidad de variedades campesinas en la sierra central

del Perú (Huánuco). Zonas Áridas., 15(1), 110-127.

doi:10.21704/za.v15i1.111.

Vimos, N., Nieto, C. & Rivera, M. (1993). El melloco,

características, técnicas de cultivo en ecuador. Ecuador. Instituto

Nacional Autónomo de Investigaciones agropecuarias.

Viteri, C., Camino, M., Robayo, D., Moreno, T. & Ramos, M.

(2020). Alimentos sagrados en la cosmovisión andina. Revista Ciencia e Interculturalidad,

27(02), 173-189. https://doi.org/10.5377/rci.v27i02.10442

![]() DOI: 10.57201/IEUNA2313312

DOI: 10.57201/IEUNA2313312![]() , Universidad

Nacional de Asunción.

, Universidad

Nacional de Asunción.![]() , Centro

de Desarrollo e Innovación Tecnológica (CEDIT)

, Centro

de Desarrollo e Innovación Tecnológica (CEDIT)![]()

![]() , Edna Fabiola

Valdez-Hernández2

, Edna Fabiola

Valdez-Hernández2![]() *, Leonardo

Martínez-Cárdenas3

*, Leonardo

Martínez-Cárdenas3![]() , Francisco

Javier Díaz-Nájera4

, Francisco

Javier Díaz-Nájera4![]() y Sergio Ayvar-Serna4

y Sergio Ayvar-Serna4![]()