Amplificando

el estado de estar entre dos realidades o identidades de los profesores de

inglés en sus

experiencias en la construcción de paz

Universidad Distrital Francisco José de Caldas,

Colombia.

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-6655-2041

e-mail: yaldanag@udistrital.edu.co

Recibido: 15/12/2023

Aprobado: 10/3/2024

ABSTRACT

Peace studies and Applied Linguistics (AL) to English language teaching complement each other. In the second field, domains such as peace linguistics appear. This manuscript contributes to this de-instrumentalized field and its domain. This inquiry approached English language teachers’ experiences in peace construction from diverse Colombian territories where dehumanizing practices perpetuate. Some formal proposals towards peace constrain English language teachers’ agencies and bodies. However, their alternative positions, and doings in peace construction otherwise, transcend instrumental goals of the liberal peace. This study amplified English language teachers’ voices to access their experiences from decolonial postures critically nuanced. Theoretical foundations conceptually discuss peace construction, experiences, and voices. This qualitative inquiry problematized narrative design and decolonial doing to create a methodological option called Otherwise Intuitive Undoings (OIUs). Its constitutive decisions were multimodal encountering, and comaking resenses to react to traditional data analysis. This intersected narrative analysis and crystallization to challenge rational treatments of what mainstream researchers demand as data analysis. Findings amplify spiritual sensing-thinking from English language teachers’ experiences in-between, which characterize for their dynamics and discontinuities. Third spaces herein constitute places where pluridimensional experiences occur, and bodies-selves transform through an acquired elasticity. Disruptive knowings, becomings, and doings in peace construction reflected the creative power of English language teachers’ bodies-selves. Note that the methodological option represents a contribution herein, crafted throughout the path. OIUs became an option in a line of flight that resisted some de-humanizing research principles, while resulting from English language teachers’ engagement with methodological decisions. Conclusions and implications synthesize systemic relationships among peace studies and AL to ELT for inspiring researchers. Third spaces from English language teachers’ amplified experiences deserve re-existence. Precisely, hearing our already existing voices, –as claimed in this study from the beginning–, rather than voicing the marginalized or the inexistent, opens a neglected debate about ethics in decolonial and critical postures.

Keywords: peace construction; in-betweenness; voices; experiences; English language teachers; decoloniality.

RESUMEN

Los estudios de paz y la enseñanza del inglés se apoyan y complementan mutuamente. En efecto, la lingüística aplicada a la enseñanza del inglés incorpora dominios como la lingüística de paz. Este artículo contribuye al campo y dominio mencionados como escenarios desinstrumentalizados. Específicamente, se abordaron las experiencias de los profesores de inglés en la construcción de paz desde diferentes territorios colombianos donde varias prácticas deshumanizantes persisten mediante conflictos distintos. Algunas propuestas formales para la construcción de paz limitan las agencias y cuerpos de los maestros de inglés desde sus territorios. No obstante, sus posiciones alternativas y los conocimientos derivados de sus experiencias al construir paz sobrepasan los propósitos de la paz liberal. Este trabajo amplificó las voces de profesores de inglés para acceder a sus experiencias desde posturas decoloniales con matices críticos. Los fundamentos teóricos discuten conceptualmente la construcción de paz, las experiencias y las voces. Esta investigación cualitativa problematizó el diseño narrativo y el hacer decolonial para crear una opción metodológica denominada: Des-haceres intuitivos otros. Las decisiones constitutivas de esta opción incluyeron los encuentros multimodales como un recurso para la co-construcción de conocimientos (Aldana, 2022), y la co-elaboración de sentidos otros como una alternativa ante procesos canónicos del análisis de datos –en el lenguaje de la investigación tradicional–. Esta consistió en la interseccionalidad entre algunos principios del diseño narrativo y la cristalización para tensionar el tratamiento racional de aquello que la investigación moderna entiende como datos y su análisis. En los hallazgos, los sentipensares espirituales se discuten desde las experiencias amplificadas de los maestros de inglés en sus terceros espacios caracterizados por sus dinamismos y discontinuidades. Dichos espacios entre-medios constituyen terceros espacios donde ocurren experiencias pluridimensionales silenciadas de los profesores de inglés y se transforman sus cuerpos elásticos. Diversos conocimientos disruptivos, posiciones y haceres en la construcción de paz reflejaron el poder creativo de las subjetividades de los profesores de inglés y su corporeidad. Cabe subrayar que la opción metodológica propuesta constituye una contribución de este estudio elaborada en el camino. Esta propuesta en fuga resiste la investigación cualitativa tradicional, y emergió del entretejer investigativo para abordar la sub-pregunta acerca de las reacciones e involucramiento de los profesores en las decisiones metodológicas en este estudio. Las conclusiones e implicaciones reiteran las relaciones sistémicas entre los estudios de paz y la lingüística aplicada a la enseñanza del inglés desde la lingüística de paz y las experiencias, en tanto fuentes relacionales de conocimientos otros. Los terceros espacios desde las experiencias audibles de los profesores de inglés merecen re-existir en el campo. Justamente, amplificar nuestras ya existentes voces –como se propuso en este trabajo desde su emergencia–, en lugar de otorgar una voz al marginalizado o lo inexistente, sugiere la apertura a un debate descuidado sobre las éticas en las posturas decoloniales y críticas.

Palabras clave: construcción de paz; entre-medios; voces; experiencias; profesores de inglés; decolonialidad.

Introduction

Peace studies as an interdisciplinary field entails inter-epistemic dialogues with areas, including theology, history, sociology, politics, economics, and Applied Linguistics (AL) to English Language Teaching (ELT). Although the last field involves neoliberal and instrumental ends (Aldana, 2021a; Hurie, 2018), its reach extends into re-humanization. English language teachers relate research and pedagogical practices to extra-linguistic purposes such as peace construction (peace studies’ core); however, their experiences are silenced. This inquiry attempts to co-understand English language teachers’ experiences behind peace construction in-between. Emerging knowledges (De Sousa-Santos, 2018) derive from embodied intersectionality, involving multifaceted lived phenomena.

In the next sections, a theoretical discussion on relevant concepts unfolds as a reflection on peace construction, experiences and voices. This supports the possible but denied relationality between peace studies and AL to ELT. Afterwards, the methodology crafted, which problematizes taken-for-granted strategies in qualitative research, appears (Aldana, 2022). This study’s methodological decisions deem horizontality and embodiment relevant to create spaces for harvesting knowledges, beyond collecting (mining) or analyzing them. It smoothed the creation of the Otherwise Intuitive Undoings (OIUs) as an option for inquiring that denaturalizes rational philosophical frameworks of educational qualitative research (Aldana, 2022).

Findings sense-think English language teachers’ elastic subjectivities when their bodies transited throughout pluridimensional experiences in third spaces. Amplifying these teachers’ voices to co-understand their experiences made their productive tensions and struggles in-between not only visible but sensed. These teachers challenged instructor and constructor roles, when living creative resistances (De Sousa-Santos, 2018) differently. This study approached an everlasting in-betweenness where diverse teachers’ beings, knowings, and doings (De Sousa-Santos, 2018) were produced. Within third spaces, “an other” (Mignolo, 2012, p. 66) roles and experiences reflected pluriversal life positions. Third spaces were relational to these teachers’ elastic selves. Indeed, neither in-betweenness nor OIUs were prescriptively created through dichotomies. Herein, these teachers’ third spaces are “not simply one thing or the other, nor both at the same time, but a kind of negotiation between both positions” (Bhabha, as cited in Byrne, 2009, p. 42). Recalling Bhabha (as cited in Byrne, 2009), they entail “doubleness or splitting of the subject” (p. 42). In-betweenness of these teachers’ different communal experiences in peace construction displayed multidirectional movements. This inquiry sensed-thought third spaces (in-betweenness), respecting their complexity, hybridity and dynamics (Bhabha, 2004).

The ongoing methodological decisions (OIUs) in this inquiry represent crafted results, explained in the crafting box given their methodological nature. This option responds to the subquestion addressing how English language teachers felt this study’s methodological (who-how) decisions. Thus, these teachers inspired methodological decisions, which constituted disruptive participation herein (Aldana, 2022). The resulting OIUs as a peace-driven option sought co-existence (reciprocity), rather than denying available methodologies; it resists colonizing (silencing) logics. OIUs are neither a finished option, nor another recipe for educational inquiry in ELT. Everlasting adjustments subject to re-shaping are expected in contexts where they become relevant.

In this spirit, conclusions and implications synthesize English language teachers’ embodied experiences in peace construction from third spaces to underscore intersectionality between AL to ELT and peace studies as interdependent fields. This alliance allowed for resignifying lived (created) experiences in-between. Various implications are discussed, suggesting a neglected ethical debate in decolonial postures critically nuanced within ELT.

Theoretical background

A De-instrumentalizing departure

Discussing theoretical concepts entails interdisciplinarity and transdisciplinarity for AL to ELT and peace studies relationality. The modern mode of objectification that assigns disciplines a monolithic interest (Foucault, 1982) produces reductionist readings of life complexities (Maldonado, 2021). Counteracting, hybrid dialogical ways to read our worlds appear: interdisciplinarity and transdisciplinarity. The former urges connections among disciplines (Maldonado, 2021), and the latter favors disciplines’ interactions towards reciprocal transformations, since boundaries disappear (Maldonado, 2021). Namely, multidisciplinarity is insufficient for inquiring; transformative interactions among knowledges, methodologies and bodies address wholeness (Morin & Delgado, 2014). Sanitizing disciplines hinders transdisciplinarity especially.

Consequently, I resist purist epistemological positioning (Aldana, 2022) as though it were a monolithic option to select and watch out. From the first time I problematized my body-self concerning interpretive frameworks (Cresswell, 2018), an ethical/political decision was crafted: I felt decolonial postures mattered if articulating critical perspectives. Questions of power (e.g., inequalities, injustice, hegemony, domination…) were tackled, without ignoring social and epistemological inexistence (forced disappearance). Critical and decolonial postures are complementary (Aldana, 2022). This epistemological cooperation re-humanized this inquiry by transcending the attitude of selecting/taking trendy decisions. Although some academists framed this inquiry within decoloniality only, even when epistemological mestizaje was openly supported (Aldana, 2021a, 2022), I contest it through weaving critical and decolonial relationalities where their differences become contributions, rather than warnings. Research decisions, including epistemological ones, are created more than selected.

Peace construction in ELT: A peace linguistics becoming

Towards re-humanizing AL, English language teachers embark on extralinguistic journeys. English becomes a tool to approach sociocultural realities in a discipline de-instrumentalized through interdisciplinarity and transdisciplinarity. Extralinguistic goals from critical and decolonial postures encompass phenomena as social justice or peace construction, which are different but relational. The former constitutes the counter-conduct to social injustice in dialectical relationships (Freire, 2015). Social justice combines epistemological sovereignty and cognitive justice (De Sousa-Santos, 2018). Therein, the oppressed, and leaders (educators) engage in solidarity struggles for humanization (Freire, 2015) towards sociocultural impact on societal institutions, including education. Contrastively, peace construction pursues more than absolute harmony as opposed to direct violence (Galtung, 2016), and social injustice. Constructing peace becomes a multifaceted concern, process, and experience towards diverse beings’ co-existence.

Peace construction diversities produce plural opportunities for AL to ELT to join its configuration through a long trajectory domain called peace linguistics. It problematizes language use, since it is neglected in peace studies research (Curtis, 2018). Gomes de Matos (as cited in Curtis, 2018) asserts peace linguistics examines “how people could and should communicate with each other in ways that are respectful, compassionate and peaceable” (p. 3) to avoid violence. When Gomes de Matos (2018, p. 290) distinguishes “communicating about peace” from “communicating peacefully”, languages seem constitutive to peace construction. Other than reified linguistic systems, they become resources mediating peace-driven communication towards social rapport. Namely, the linguistic dimension of languages remains, but its purpose is re-humanized.

Peace linguistics in AL to ELT poses this question: “[h]ow can language users and methods-materials for language education be further humanized linguistically?” (Gomes de Matos, 2014, p. 416). This question relates peace and language to didactic decisions. Re-humanizing ELT through the language of peace assists learners to become peace language users (Oxford et al., 2018). Peace linguistics overlaps nonkilling linguistics, which advocates languages use “in all their peace-making potential” (Friedrich & Gomes de Matos, 2012, p. 17). It disrupts coded violence since conflicts could be solved through language that avoids harm (Gomes de Matos, 2014; Friedrich & Gomes de Matos, 2012). Communicative dignity and a nonkilling mentality can guide interactions using languages (Friedrich, 2012). Peace linguistics in AL incorporates uncertain open-endedness and hybridity (Bhabha, 2004), which make it a domain becoming in flux where “static meanings or essences” (Ellingson, 2017, p. 7) are problematized.

Experiences and voices: more than trendy concepts

From its beginning, this inquiry manifested an interest and curiosity regarding experiences and voices. Although we, as English language teachers, had various stories about what we lived and created in peace construction, we felt unauthorized to pronounce them. When interacting with teachers who collaborated in this inquiry, voices and experiences became relevant. They were more than prescribed theories or trendy utilitarian concepts for reifying trivial purposes. This study challenges the fetishization of these concepts to resist instrumentalizing agendas (Larrosa, 2006).

In this spirit, those concepts and methodological tools were problematized. One commonality is their inclusion in traditional, critical, and postcolonial research. Their use is not exclusive to transformative frameworks and qualitative research. Experiences and voices as research interests occur in diverse research; the difference is their conceptualization, which varies from instrumental to re-humanized. These concepts’ ubiquity across scholarship justifies their relevance.

Some particularities inside experiences concept occur. The scientific method and postpositivism approach the experience –in singular– rationally as a mechanism for hypotheses’ verification (Bunge, 2013). This experience is captured through observation (Bunge, 2013), as though it happened in subjects’ outside realms. When the experience occurs inside, it is described as “personal experience in the form of common-sense knowing” (Cohen et al., 2018, p. 4) to adjust through reasoning (Bunge, 2013). Thereby, this concept is reduced to an abstract account of events rationally observed in a setting.

Alternative conceptualizations about experiences –pluralized– resist postpositivist versions. The sociology of experience (Dubet, 2010) explains a transition from action to experience occurs, while social and critical factors intersect in its construction. Then, lived experiences constitute created experiences, because approaching our lives therein entails creativity. These are produced than simply appearing in exteriorities, the places of experiences are our bodies (Larrosa, 2006). Co-understanding experiences demands sensitiveness to multifaceted relationships between fluctuating sociocultural settings, and alive bodies-selves participating in their representation and transformation (Freire, 2019).

Thus, decolonizing experiences concept implied critical nuances. Freire (2019) argues experiences ground in everyday life. Consequently, sociocultural phenomena, including power issues, are relational to experiences. Marginalization, domination, empowerment, emancipation and resistance appear in the critical study of experiences (Freire & Macedo, 2011). Interestingly, Larrosa (2006), Freire and Macedo (2011) remark educators’ role in transforming experiences even outside schools. Experiences are subject of transformation while changing those who live them (Larrosa, 2006; Freire, 2019).

Problematizing experiences concept softly hints the voices notion. As experiences comprise linguistic, communicative, sociopolitical and cultural phenomena (e.g., silencing), voices became consubstantial to them, producing embodiment. Voices are material channels to access experiences, constituting another interdisciplinary concern in humans’ lives. De Sousa-Santos (2018) considers diverse voices coexist with the unpronounceable. Guha (2002) underscores small voices of oppressed groups to struggle “against oppression and domination in the world at large” (De Sousa-Santos, 2018, p. 12). Besides physical waves in our phonoarticulator system, voices resonate power uses/abuses, when turned up, down or silenced.

Pluralizing voices challenges its trendy homogenizing use. Since teachers are complex and diverse, the voice requires pluralization as social justice (De Sousa-Santos, 2018). Guha (2002) and De Sousa-Santos (2018) acknowledge multiple voices, including the oppressed ones. Guha (2002) names these voices small, because they are in the civil society “drowned in the noise of statist commands” (p. 307). Nonetheless, these small voices are diverse, complex, and insurgent; their owners have stories to tell, even when silenced (Guha, 2002). De Sousa-Santos (2018) invites us to hear “stifled voices of the oppressed, to whom only subaltern orality was generally available” (p. 61). The voice of authority exerts hierarchical “power of arms” over voices of suffering whose “power of truth” makes themselves heard (De Sousa-Santos, 2018, p. 92).

Crafting a tool box

When problematizing qualitative research (Aldana, 2022), critical and decolonial postures smoothed its de-monumentalization (De Sousa-Santos, 2018). It unnaturalizes qualitative research principles enacting inequalities and colonial mechanisms, which disappear alternative beings, knowings, and doings. The subject-object relationships and extractivism as latent principles persist in qualitative research (Aldana, 2022; Vasilachis, 2009), constituting a colonial matrix. Problematizing certain principles of narrative inquiry and the decolonial doing informed the Otherwise Intuitive Undoings (OIUs) whose characteristics and decisions (Aldana, 2022) are crafted, and discussed next.

In OIUs, English language teachers re-existed towards cognitive and social justice (De Sousa-Santos, 2018). One decision in OIUs consisted of inviting teachers to decide how they wanted to be invoked, rather than assigning them a label. This contributes to re-humanize methodological decisions made together, horizontally, towards non-dehumanizing research (Ortiz et al., 2018). Rooted in Ubuntu wisdom (Msila, 2015), OIUs resignified methodology as “who/how” decisions (Aldana, 2022, p. 133). They remark collective relationality (interconnectedness, togetherness…), and life complexity.

Unexpected interactions happened with English language teachers as known subjects and knowers simultaneously (Vasilachis 2009; Aldana, 2022) in OIUs. These teachers shared their experiences in peace construction and who-how decisions through modes permanently crafted. We decided it for feeling instrumentalized in previous research and pedagogical work. Known subjects and knowers proposed interactions in OIUs. Sharing power yielded emerging “sites of [border] co-constitutive interaction” (Bruyneel, 2007, p. xix), creative co-production of knowledges (De Sousa-Santos, 2018), and contestation (Butler, 1995).

Collaborators were seven, and they displayed characteristics that made them relevant guests. They are Colombian in-service English language teachers with peace construction proposals inside urban and semi-urban territories. These teachers were willing to share their particular stories behind peace construction. They lived in formal and informal scenarios, which silenced their inspiring experiences. This inquiry problematized overgeneralizations about them to resist essentializations (Aldana, 2022).

In OIUs, a

resource to co-construct knowledges was proposed, and transformed from

multimodal encounters to encountering (Aldana, 2022).

Notwithstanding their relationship to data collection methods,

multimodal encounters/encountering as resources keep critical

differences from the former. They resignify communication relationships in

qualitative research where who and how were relational to make

encountering a re-humanized decision for co-constructing knowledges (Aldana,

2022), beyond recipes-driven and extractivist/hierarchical methods. Indeed, we

created a linguistic reference to power sharing when alternately proposing

interaction possibilities for encountering. The baton became the word

herein that indicated who orchestrated them. That who-how decision of

this study decentralizes power, while creating languages to resignify

transformed interactions. Camaraderie therein produced feelings of ableness

and freedom absent in hegemonic methods. It contested subject-object

relationships, and permitted who-how decisions to emerge (Vasilachis, 2009;

Aldana, 2022). When problematizing and counter-reacting to canonical research

through multimodal encountering, closeness, reciprocity, horizontality,

affective safety, semiotic convergence, and complementarity became crucial for

co-constructing knowledges (De Sousa-Santos, 2018; Mignolo, 2012; Aldana, 2022)

inside OIUs as methodological disobedience to research colonialities.

Multimodal encounters/encountering differ from interviews and narratives of mainstream qualitative narrative designs, which subtly privilege rationality, hierarchy and semiotic isolation. Narrative inquiry in the epistemologies of the North ignores the “body in all its emotional and affective density”, objectifying and making it an absent presence (De Sousa-Santos, 2018, p. 88). Modernity remains in narrative inquiry, when coding body in singular (Barkhuizen et al., 2014). Hence, “the body as an ur-narrative, a somatic narrative that precedes and sustains the narratives of which the body speaks or writes” (De Sousa-Santos, 2018, p. 88) is missing. Narrative inquiry supports the OIUs, but colonial heritage in the former constrains embodiment sensed (produced) in this inquiry.

Thereby, decolonizing methodologies such as the decolonial doing (Ortiz et al., 2018) gained relevance. Albeit problematizing the colonial background of research (Tuhiwai, 2021) in social studies, and resignifying it as doing allow for approaching social realities (Ortiz et al., 2018), modern heritage persists. Decolonizing notions for inquiring our worlds/realities could not deny existing research theory. Pluriversality favors “decolonization, creolization, or mestizaje through intercultural translation” to avoid massive epistemicide (De Sousa-Santos, 2018, p. 8). A radical boundary between mainstream qualitative research with its language, and decolonial options, would craft another masked modernity, which is far from coexistence inside pluriversality (De Sousa-Santos, 2018). Decolonial doing could harness and add the with, when advocating proposals otherwise in/from/by/for their contexts of emergence (Ortiz et al., 2018). Consequently, the monolithic discourse behind the decolonial doing reverses, while pluralizing it, and embracing undoing (De Sousa-Santos, 2018).

Problematizing qualitative research data analysis underscored creation. Conventionally, that stage demands the researcher –usually alone– to interpret data towards the so-called analysis categories (Cohen et al., 2018; Denzin & Lincoln, 2018). It depends on researchers’ interpretive frameworks/positionings (Creswell, 2018), and approaches to apply therein. However, the same purpose to do something with data endures: analysis. Furthermore, modern academies demand this decision before collecting data, for their research rigidity and linearity (Aldana, 2022). Qualitative inquiry as living (Aldana, 2022) resignified data analysis as comaking resenses to complement who-how decisions inside OIUs. It materialized both simultaneously and after co-constructing knowledges in multimodal encountering(s).

Comaking resenses differs from data analysis. First, the collective nature of comaking made it a shared process with English language teachers, when resignifying/interpreting our experiences herein. Second, it avoided dissecting/separating experiences in peace construction, in contrast to patterning data analysis (Cohen et al., 2018). Thirdly, creation/creativity supported comaking resenses, as knowledges otherwise were crystallized (Ellingson, 2017). Crystallized products included a comic (multimodal) book linked to some videos, and recorded re-storying in a radio station.

Finally, another who-how decision in OIUs supported comaking resenses, namely garabatear. It combined doodling and drawing in a personal journal to express our sensations around multimodal encountering(s) once finished. This who-how decision arose when extra experiences required attention. Garabatear has psychological, linguistic, and sociocultural connotations. Psychologically, garabatear describes children’s development stages when playing with written and visual languages (drawing) (Buffone, 2023). Moreover, it supports teaching towards comprehension and creativity (Cantón, 2017). Culturally, it evokes the Garabato dance during carnivals in Colombian Caribbean territories. Although a universal history on its origin is unattainable, this dance relates to afro communities in colonial slavery, and a peasant dance (Universidad Autónoma del Caribe, 2020). This colorful danced fight between life and death represents black slaves mocking their masters, and own disgrace. Sadness, happiness, irony, sarcasm, and creativity characterize this dance where life overcomes death (Universidad Autónoma del Caribe, 2020). Garabatear for comaking resenses made tensions and struggles louder, while empowering our creative selves.

Findings

Amplifying our in-betweenness

This inquiry aimed at co-understanding English language teachers’ experiences in peace construction. Some spiritual sensing-thinking –sentipensares espirituales– (Fals-Borda, 2015) after comaking resenses are discussed as knowledges otherwise from resignified bodies-selves and experiences. Unlike reified rational categories, these knowledges (De Sousa-Santos, 2018) problematized modern separations of mind and body to co-understand what English language teachers lived when “acting with the heart using the head” (Fals-Borda, as cited in Botero-Gómez, 2019, p. 302) in-between, considering their amplified voices.

Spiritual sensing and knowing (Mignolo, 2011), feeling-thinking (Palacios, 2019), or sensing/thinking (Pinheiro-Barbosa, 2020), as translations of sentipensar and sentipensante (Fals-Borda, 2015), are geopolitically situated herein. Colombian violence(s) and aftermath affect English language teachers’ territories directly and indirectly. Although no official date indicates the start of Colombian violence, scholars agree it began on April 9th, 1948, when Jorge Eliécer Gaitán, a presidential candidate, was murdered. It triggered conflicts between the Liberal and Conservative parties during a long wave of violence. Nowadays, these political ideologies manifest through different parties whose conflict remains, hurting social leaders and activists (INDEPAZ, 2023).

Living constitutive tensions in third spaces: becoming instructors or constructors?

Hearing experiences behind peace construction in ELT amplified everyday (pedagogical) practices and attached becomings. Liberal peace establishes fixed knowing, being and doing for English language teachers. Despite power institutional structures such as the Ministry of Education (MEN), UNESCO, the British Council, or the Centro de Memoria Histórica (CMH), these teachers become authors of resistances (De Sousa-Santos, 2018) to construct peace, and differently becoming in those third spaces. However, they overlap non-being zones (Fanon, 2010), even when producing relevant knowledges in flux (De Sousa-Santos, 2018).

Peacebuilding, peace education, and English for peace constitute formal proposals on peace as citizenship, human rights, conflict resolution, and the opposite to war (Aldana, 2021b). Notwithstanding formal peace grounds in good-practices (instrumental), and universalizing discourses to shape teachers’ beings and pedagogical practices (Aldana, 2021a) in first spaces, English language teachers challenge them (Excerpt 1), moving to lines of flight, leaving instructor roles.

Excerpt 1

I feel I instruct peace when I must teach contents, considering the Chair in peace, and UNESCO’s toolbox for peace education. However, I sometimes adjust these guidelines to feel freer, as a creator or constructor of peace with students. Illustrating, I don’t teach human rights contents only, but I address them regarding the Nature’s rights for living differently. We developed projects about our concern and love towards the environments where we live.

English language teachers produce in-between sites (Bhabha, 2004) where they resist and co-exist (Walsh, 2017) transcending epistemological obedience. These teachers construct knowledges from their interstitial positions (Bhabha, as cited in Byrne, 2009). In excerpt 1, this teacher understands the formal role (instructor) demanded to adopt overgeneralizing toolboxes. However, his decision about adapting institutionalized guidelines reflects a political claim of his right and capacity to create collective alternatives (De Sousa-Santos, 2018) towards peace. Collective interests challenge hierarchies in ELT third spaces (Excerpt 1) and liberal peace (Fontan, 2013).

Tensions when experiencing peace construction in-between instructor, and constructor/creator positions implied an emotional cost to English language teachers. An affective dimension (Benesch, 2012) of embodied experiences becomes louder. When advised to assume one role, a teacher expressed her emotional reaction (Excerpt 2), underlining her sensitiveness to violence, which fueled her empowering emotionality. Despite the rational peace educator and sanitizer –in liberal peace (Fontan, 2013)–, or the peaceful teacher of the XXI century (Aldana, 2021a), these teachers’ emotivities yield power moves (Benesch, 2012). It explains why the rational peace educator seems unauthorized to feel (Benesch, 2012), even when peace involves an inner dimension claiming embodiment (Aldana, 2021b; Ellingson, 2017).

Excerpt 2

I couldn’t be only an instructor or an educator. I was shocked when my colleagues told me to play one role, and it wasn’t necessarily the latter. But this combination of panic, surprise, loneliness, stress, bitterness… urged me to continue with this peace initiative. I realized listening to students’ stories was a powerful start.

The political side of teachers’ emotivities (Benesch, 2017) supports resistances (De Sousa-Santos, 2018) in-between as scenarios of contestation (Bruyneel, 2007) to liberal peace. Third spaces constituted places to re-create peace construction and English language teachers’ roles through proposals such as communitarian pots (Excerpt 3). When adapting more than adopting liberal peace, teachers’ emotions in silence and socially unjust situations (Excerpt 2) moved them. Their voices amplified affective forces making them transit throughout selves that involved “modes of being, including emotional comportments, expressions, postures, movements and touch” (Ellingson, 2017, p. 86). Experiencing the instructors-becoming demand provoked a re-humanizing need in-between to intersect diverse positions. These transcended the instructor and constructor/educator tension. Next lines deepen this in-betweenness (Bhabha, as cited in Byrne, 2009).

Excerpt 3

Although colleagues told me not to do it [the communitarian pot], students and the community members participated. Dancing, food, and the school batucada appealed more neighbors to collaborate. I was delighted.

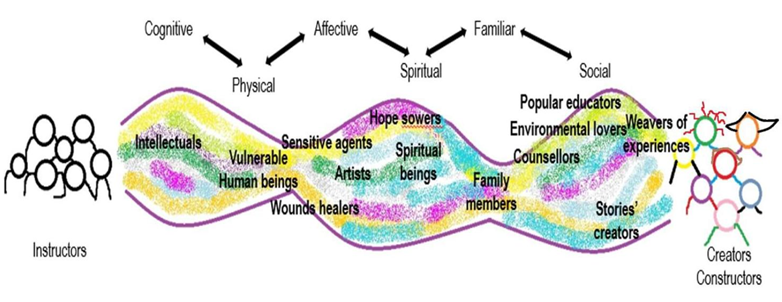

Living in-between instructors or creators

Amplifying English language teachers’ experiences lets us resignify tensions within third spaces where they challenged rational being, knowing, and doing (De Sousa-Santos, 2018) in peace construction (Aldana, 2022). In-between, teachers’ knowings, doings, and becomings in flux (Ellingson, 2017) produced hybridity. Their bodies-selves moving in-between instructors and constructors (Figure 1) challenge dichotomies through multidirectional movements towards lines of flight (Ellingson, 2017). These teachers’ experiences in peace construction were pluridimensional and interdependent. Tensions were constitutive and relational to complex selves in-between (Excerpt 1).

Dual and negative meanings of tensions (McDonough, 2017) vanished in third spaces. Tensions became constitutive in pluridimensional experiences, which made teachers' selves (subjectivities) elastic, while bodies moved (Webber, 2012). Experiences in peace construction encompassed multifaceted “borderline existences” (Byrne, 2009, p.127) that exceeded Cartesian rational subjects (De Sousa-Santos, 2018), and the instructor-constructor tension. They arose and intersected through action and embodiment. Figure 1 displays these teachers’ bodies-selves in peace construction across louder experiences. Next lines sense-think them in third spaces (in-betweenness), challenging normalized violence-driven (Padilla & Bermúdez, 2016) silencing mechanisms. Transitional leaps/moves articulate these teachers’ embodied experiences in peace construction.

Figure 1. English teachers’ elastic selves in-between

Teachers’ transitional selves are relational to their multifaceted experiences within complex territories. In Excerpt 4, this teacher became a counselor inside familial and intergenerational conflicts at the school. This teacher invited her student to reflect empathetically about her mother, and created a values seedbed with students where she was a popular educator, but she felt as a social values promoter, and a learner. As a sower of social values seeds in her peace construction experiences, her third space let her recycle resources from first (her and students’ families, sociocultural surroundings) and second spaces (educational environment) towards her students’ welfare.

Excerpt 4

I told this student to understand her mother. What her mother did was not appropriate, but she could think for a while how her mother was educated as a child… In this values seedbed, I felt as learning from students.

These teachers experienced different becomings as fugitive selves (Asenbaum, 2021), while jumping in-between throughout sites of contestation (Butler, 1995). In peace construction otherwise, these teachers embodied it across pluridimensional experiences. Their voices (excerpts 5 and 6) challenge dichotomous experiences (mind-feeling), for additional embodiments to amplify such as spiritual and physical ones (Ellingson, 2017). Again, forces moved teachers’ bodies, making their selves elastic across pluridimensional experiences. A teacher experienced struggles (excerpt 5) concerning the anthropocentric, non-spiritual, rational subject privilege in modernity where separating science, art and spirituality towards sanitization (Ellingson, 2017) prevails. In Excerpt 5, AR’s voice suggests English language teachers’ spiritualities seem forbidden (e.g., Christianity). It restates peace construction occurs in disembodied ELT academies. UB and AR (Excerpt 5) shared their spirituality, and experienced scorn for it, when constructing peace. Stigmatization towards teachers intersects spiritual, racial, gendered, cultural, epistemological, and disciplinary selves.

Excerpt 5

AR: Criticism for being an English teacher who constructs peace is not enough; further reasons appear: my condition as a Christian.

UB: Really? I lived something similar… Besides, some demanded me to be a model of perfection just for researching upon peace. I got so stressed that I did meditation.

Likewise, experiences in peace construction are physically and psychologically enfleshed through English language teachers’ material bodies in-between. In excerpt 6, SS relates students’ structurally violent (Galtung, 2016) experiences to her physical and mental health. These teachers lived anxiety, sadness, and frustration for contextual and institutional constraints (Excerpt 1, Excerpt 6). Their emotionalities (Benesch, 2012) moved teachers in-between, producing physical and psychological experiences (Excerpt 6). When constructing peace in ELT, teachers’ “consciousness is always and only embodied, holistically integrated into the enfleshed subject” (Ellingson, 2017, p. 16). Namely, “[b]eing and knowing cannot be easily separated” (Ellingson, 2017, p. 16). Dichotomies for explaining third spaces produce trivial reductionist understandings of experiences (Aldana, 2022) in peace construction.

Excerpt 6

SS: Once I heard they [students] were in illegal groups, I felt worried, sad, and even physically exhausted. I came back home with a terrible headache.

Similarly, English language teachers lived stereotypes in third spaces. UB (excerpt 5) felt marked through overgeneralizing images about peace researchers as superhumans who never have conflicts. An objectifying mechanism homogenizes teachers in peace construction, drawing on de-humanizing neocolonial discourses. Rather, teachers are alive and feel emotions such as anger (Excerpt 5), or even get sick (Excerpt 6). These teachers’ bodies and vulnerability seem denied (Ellingson, 2017). Universalizing liberal peace (Fontan, 2013) reappears to homogenize the white rational peaceful teacher of the XXI century (Aldana, 2021a).

Nevertheless, English language teachers’ suffering experiences silenced (Excerpt 7) transform through teachers’ creative power behind their elastic selves (Webber, 2012). This elasticity seems consubstantial to creative power behind alternative knowings and doings that mirror life and peace dynamics in counterspaces (Bhabha, 2004). These teachers’ vulnerable selves aforementioned represented more than weakness; they became empowered and empathetic bodies-selves who creatively moved throughout plurimensional experiences.

Excerpt 7

EO: We as teachers suffer in silence.

Considering AR’s voice, his leaps intersected academic, familial and personal experiential dimensions (Ellingson, 2017). They articulated roles as a peace educator, healer, agent, father, neighbor, Nature caregiver, spiritual Christian teacher, and an artist. AR shared it, when re-signifying experiences behind his proposal called: the Blue House. Therein, peace construction as social justice reduced socioeconomic inequalities in the marginalized locality of his childhood (Excerpt 8). In-between, AR re-signified English as a right (Hult & Hornberger, 2016) that fosters peace construction, as long as its learning was guaranteed to everybody, regardless of socioeconomic status (Excerpt 8).

Excerpt 8

AR: The idea that English learning is a right of everybody inspired this initiative. As I lived in a low socioeconomic status neighborhood, I wanted to help these children in similar conditions to have access to English. For me, it is social justice.

The abovementioned political side of spiritualities and emotions (Ellingson 2017), including those from suffering also works (Excerpt 9) towards re-humanizing empathy (Excerpt 8). More than putting ourselves on someone else’s shoes, it consisted of placing ourselves on/in others’ skins. The power of healing behind the word “scar” in UB’s voice (Excerpt 9) reflects this embodied empathy in-between, which supports teachers’ strength, sensitiveness and resilience for sensing others’ skins. Teachers’ bodies-selves gained elasticity throughout their suffering and healing experiences. Their bodies’ outer and inner phenomena connected, when moving and making selves elastic (Excerpt 10).

Excerpt 9

UB: This scar represents my students’ suffering and mine, when seeking someone who supported us in our peace project, but also how we got stronger afterwards.

Excerpt 10

SS: As a teacher and a counsellor, I am in charge of myriad school issues. I have faced terrible situations, as the kid who committed suicide.

English language teachers’ experiences and creative knowledges under a low profile (in-between) deserve hearing towards alternative power uses. The creative power behind these teachers’ selves made “an other” (Mignolo, 2012, p. 66) bodies possible in peace construction, challenging totality. I borrow the term an other from Mignolo (2012) to characterize this power. It provokes coexistence among ways of knowing, being and doing, embracing uncertain (Denzin & Lincoln, 2018; Savin-Baden & Howell, 2010; Aldana, 2022), ongoing, unfinished, and countless unmodern possibilities for pluriversal (De Sousa-Santos, 2018) living.

In-betweenness allows our experiences in peace construction to become relational. Beyond instructors and constructors/creators tensions, further selves and knowledges (De Sousa-Santos, 2018) intersected. These challenge colonialities of power, being and knowing (Castro-Gómez & Grosfoguel, 2007) that endure in ELT (Macedo, 2019), when instrumentalizing peace (Hurie, 2018; Aldana, 2021a). What is disruptive (Ellingson, 2017) about these third spaces is English language teachers’ resistances and re-existences (Walsh, 2017) through their elastic selves in-between (Excerpt 10). Teachers’ experiences involved their bodies moving, and selves’ elastic transformations as non-prescribed (unimagined) roles in peace construction (Excerpt 10). Sensing-thinking these teachers’ silenced experiences and elastic subjectivities (Butler, 1995) contests ELT colonialities.

Additionally, these teachers became weavers of experiences (Excerpt 11), and experiential layers. A layer means how someone relates to surroundings through mental holism (Geuter, 2016); English language teachers’ experiences pluralized layers. These teachers weaved students’ experiences for resignifying theirs when their bodies transited throughout life scenarios in-between, and selves became elastic (Excerpt 10). This spiritual sensing-thinking shows how relevant bodies-selves are for pluri-signifying our experiences. Unlike individually experiencing peace construction, a social dimension (Larrosa, 2006) of embodied experiences stands out in-between.

Excerpt 11

SS: …This is like weaving our experiences. I remember one indigenous child who was pregnant, I felt touched by that. I talked with her about it. I don’t know why it happens there. I knew about similar cases. I wasn’t concerned with English merely, I wanted to change that.

Teachers’ elastic selves fluctuated to self-healers. They experienced struggles with social and disciplinary inequalities owing to objectification modes (Foucault, 1982) that “transform human beings into subjects” (p. 777), making knowledge a reified object. This “dividing practice” (Foucault, 1982, p. 777) produces wounds on teachers’ bodies. The aftermath of multiple violence, e.g., structural (Galtung, 2016), and symbolic (Burawoy, 2019) exacerbated them. An English language teacher experienced violence as rejection, misrecognition and loneliness (Excerpt 12) in her third space. Contrastively, another teacher’s voice suggested healing became an intersubjective practice (Ellingson, 2017) when encountering (Excerpt 13).

Excerpt 12

UB: Hearing my colleagues frustrated me. I thought English language teachers would support me. But they didn’t. They constantly questioned the relevance of peace in ELT. A science teacher was more willing to listen to me.

Excerpt 13

LN: In these encounters, I feel accompanied; I enjoy them. Even when recalling those difficult moments in peace construction, I don’t feel the same.

Healing in English language teachers’ third spaces also occurred when their elastic bodies-selves transited to healing roles. As social healers, teachers’ interests and embodied empathy regarding social surroundings exemplify it, as AR’s Blue House (Excerpt 8) representing his desire to live without social inequalities (Excerpt 11). This proposal about creating an English language institute for social justice implies an attitude otherwise towards the oppressed (Freire, 2019), through which educators as social healers assist transitions/movements of those placed in a nonbeing zone (Fanon, 2010) to re-exist (Walsh, 2017). As environmental healers, the Nature became an alive extension (Rocha-Buelvas & Ruiz-Lurduy, 2018) of teachers’ bodies. In excerpt 1, this teacher expressed his and students’ love towards the Nature described as holding rights. It challenges the modern living/non-living dichotomy that implies the human/non-human duality. This discourse manifests in Human rights as only protecting human beings at the expense of what is nonhuman (Singh, 2018). The teacher in excerpt 1 worked with students towards horizontal connections between natural and human worlds, being alive and deserving equal care and love.

Altogether, English language teachers’ experiences and elastic bodies-selves (Figure 1) displayed their creative power in-between where dynamic knowings, becomings, and doings transformed. The elasticity of teachers’ moving bodies-selves permitted pluridimensional experiences behind peace construction where creative power was productive for re-humanization. Teachers’ roles and doings otherwise, beyond the liberal peace (Fontan, 2013), made their struggles, dilemmas, feelings, tensions, wishes, and further embodiment, sources of spiritual sensing-thinking. They “leave leeway for a significant [third space] of freedom and creativity” (De Sousa-Santos, 2018, p. 35) where these teachers resist and re-exist as weavers of experiences, spiritual beings, sowers of empathy, silenced resilient educators, healers of personal and social wounds, environmental lovers, counsellors, and peace constructors in Colombia.

Conclusions and implications: sensing/thinking the unfamiliar

This manuscript shared co-understandings around English language teachers’ experiences in peace construction from in-betweenness where diverse bodies-selves intersected. These experiences occurred inside and outside classes, and decolonial postures critically nuanced allowed for amplifying them. Methodological insights and practical decisions problematized modern research principles to craft an option (OIUs) that contested mainstream qualitative research through intuitiveness, horizontality, affectivity, spirituality, and further embodied beliefs towards who-how decisions (multimodal encountering and comaking resenses). Therein, we resignified experiences to crystallize them through a multimodal comic book.

Findings as spiritual sensing-thinking amplified communal third spaces where English language teachers’ embodied experiences in peace construction integrated disruptive life-driven knowings, and creative power. They constituted complex sources of re-humanizing knowledges. Their hybridity, horizontality, non-linearity, and de-instrumentalization illustrate creative coexistence in everyday in-between pluridimensional experiences. Elastic bodies-selves moving there contribute to peace linguistics in AL to ELT epistemologically and methodologically (Aldana, 2021b) from their experiences and empowerment. Then, ethical commitments to construct peace(s) without ignoring experiences, but hearing them through teachers’ existing voices fuels this sensitiveness to embodiment.

An implication invites the exploration of in-betweenness from wholeness (successful resistances, losses, pain, frustrations, markedness…) in vulnerable bodies-selves. Subsequent unlearnings and relearnings in peace construction become sources of political decisions to encode otherwise. It prompts creating notions for making justice to our hybrid realities, experiences, and elastic selves’ creative power in-between. Taken-for-granted categories trap us to understand third spaces.

Further implications for pedagogical and research work appear. Peace linguistics excels peace as reified contents. Pedagogical and research options could harness locally embodied peace construction by teachers through their amplified experiences in-between. Subsequently, intuitiveness complementing rationality becomes another resource for teaching and researching. Educational contexts could approach third spaces in peace construction towards living/learning together, which encompasses love in-between. Disruptive, decolonial, but especially, pedagogical love (Jiménez-Becerra, 2021) seemed consubstantial to experiences, and voices. More inquiry could address this multifaceted love linguistically and socially. Sensing-thinking it, considering third spaces’ fluidity, is relevant towards pedagogies and inquiries that denaturalize modern/colonial academies’ disembodiment. Revisiting normalized violence(s) constitutes a first decision.

References

Aldana, Y. (2022). In the path of creating a relational “How” in research. In A. Zimmerman. Methodological innovations in research and academic writing (120-142). IGI Global publishing.

Aldana, Y. (2021a). Una lectura otra sobre la construcción de paz en la enseñanza del inglés. Análisis, 53(98). https://doi.org/10.15332/21459169.6300

Aldana, Y. (2021b). Possible Impossibilities of Peace Construction in ELT: Profiling the Field. HOW, 28(1), 141–162. https://doi.org/10.19183/how.28.1.585

Asenbaum, H. (2021). The politics of becoming: Disidentification as radical democratic practice. European Journal of Social Theory, 24(1), 86–104.

Barkhuizen, G., Benson, P. y Chick, A. (2014). Investigación narrativa en la investigación sobre la enseñanza y el aprendizaje de lenguas. Routlege.

Benesch, S. (2012). Considering emotions in critical English language teaching. Routledge.

Benesch, S. (2017). Emotions and English language teaching: Exploring Teachers' Emotions labor. Taylor & Francis.

Bhabha, H. (2004). The location of culture. Routledge.

Bruyneel, K. (2007). The Third Space of Sovereignty: The Postcolonial Politics of U.S.–Indigenous Relations. University of Minnesota.

Buffone, J. (2023). Garabatear más allá del papel. Un análisis fenomenológico del movimiento en la primera infancia. Tábano, 22, 40-62.

Bunge, M. (2013). La Ciencia. Su método y su filosofía. Libreria siglo.

Burawoy, M. (2019). Symbolic Violence: Conversations with Bourdieu. Duke University Press.

Butler, J. (1995). Contingent foundations: Feminisms and the questions of postmodernism. In S. Benhabib, J. Butler, D. Cornell & N. Fraser (Eds.). Feminist Contentions. A philosophical Exchange (pp. 27-35). Routledge.

Byrne, E. (2009). Transitions: Homi K. Bhabha. Palgrave Mcmillan.

Castro-Gómez, S. & Grosfoguel, R. (2007). El giro decolonial Reflexiones para una diversidad epistémica más allá del capitalismo global. Siglo del Hombre Editores.

Cantón, J. (2017). Pensamiento visual para la creatividad y la narrativa mediante herramientas digitales. Universidad Internacional de Andalucía.

Cohen, L., Manion, L. & Morrison, K. (2018). Research Methods in Education. Routledge.

Curtis, A. (2018). Re-defining peace linguistics: Guest Editor’s Introduction. TESL reporter, 51(2) 1-9.

De Sousa-Santos, B. (2018). The end of the cognitive empire. The coming of age of epistemologies of the South. Duke University Press.

Denzin, N. & Lincoln, Y. (2018). The sage handbook of qualitative research (5th ed). Sage Publications.

Dubet, F. (2010). Sociología de la experiencia. Editorial Complutense.

Ellingson, L. (2017). Embodiment in qualitative research. Taylor & Francis.

Fals Borda, O. (2015). Una sociología sentipensante para América Latina (antología). CLACSO/Siglo del Hombre.

Fanon, F. (2010). Piel negra, máscaras blancas. Akal.

Fontan, V. (2013). Descolonización de la paz. Pontificia Universidad Javeriana.

Foucault, M. (1982). The subject and power. Critical inquiry, 8(1). 777-795.

Friedrich, P. & Gomes de Matos, F. (2012). Toward a nonkilling linguistics. In P. Friedrich (Ed.), Non-killing linguistics: Practical applications (pp. 17-36). Center for Global Nonkilling.

Friedrich, P. (2012). Communicative Dignity and a Nonkilling Mentality. In P. Friedrich (Ed.), Non-killing linguistics: Practical applications (pp. 17-36). Center for Global Nonkilling.

Freire, P. (2019). Pedagogia do Oprimido. Paz and Terra.

Freire, P. (2015). À sombra desta mangueira (11th ed.). Olho Dágua.

Freire, P. & Macedo, D. (2011). Alfabetização: leitura do mundo, leitura da palavra. Editora Paz e Terra Ltda.

Galtung, J. (2016). La violencia, cultural, estructural y directa. Cuadernos de estrategia, 183, 147-168.

Geuter, U. (2016). Body Psychotherapy: Experiencing the Body, experiencing the Self. International Body Psychotherapy Journal: The Art and Science of Somatic Praxis, 15(1), 6-19.

Gomes de Matos, F. (2014). Peace linguistics for language teachers. Delta, 30(2), 415-424.

Gomes de Matos, F. (2018). 16 Planning Uses of Peace Linguistics in Second Language Education. In C. S. Chua (Ed.), Un(intended) language planning in a globalising world: Multiple levels of players at work (pp. 290–300). De Gruyter.

Guha, R. (2002). The Small voice of history. Orient longman.

Hult, F. M., & Hornberger, N. H. (2016). Revisiting Orientations in Language Planning: Problem, Right, and Resource as an Analytical Heuristic. The Bilingual Review/La Revista Bilingüe, 33(3), 30-49.

Hurie, A. (2018). Inglés para la paz. Colonialidad, ideología neoliberal y expansión discursiva en Colombia Bilingüe. Ikala, Revista de Lenguaje y Cultura, 23(2), 333-354.

INDEPAZ [Instituto para el desarrollo y la Paz]. (31st of May, 2023). Líderes sociales, defensores de DD.HH y firmantes de acuerdo asesinados en 2023. https://indepaz.org.co/lideres-sociales-defensores-de-dd-hh-y-firmantes-de-acuerdo-asesinados-en-2023/

Jiménez-Becerra, A. (2021). El amor pedagógico: miradas a su devenir en la pedagogía colombiana. Praxis & Saber, 12(30), 1-18.

Larrosa, J. (2006). Algunas notas sobre la experiencia y sus lenguajes. Estudios Filosóficos, 55, 467, 480.

Maldonado, C. (2021). Las ciencias de la complejidad son las ciencias de la vida. Trepen Ediciones.

Mignolo, W. (2011) Geopolitics of sensing and knowing: on (de)coloniality, border thinking and epistemic disobedience. Postcolonial Studies, 14(3), 273-283.

Mignolo, W. (2012). Local Histories/Global Designs: Coloniality, Subaltern Knowledges, and Border Thinking. Princeton University Press.

Msila, V. (2015). Ubuntu. Knowers Publishing.

Ortiz, A., Arias, M. and Pedrozo, Z. (2018). Metodología otra en la investigación social, humana y educativa: El hacer decolonial como proceso descolonizante. FAIA, 7(30),172-200.

Oxford, R., Gregersen, T. & Olivero, M. (2018). The Interplay of Language and Peace Education: The Language of Peace Approach in Peace Communication, Linguistic Analysis, Multimethod Research, and Peace Language Activities. TESL Reporter, 51(2), 10-33.

Palacios, E. (2019). Sentipensar la paz en Colombia: oyendo las reexistentes voces pacíficas de mujeres Negras Afrodescendientes. Memorias: Revista Digital de Historia y Arqueología desde el Caribe colombiano, 15(31) 131-161.

Pinheiro-Barbosa, L. (2020). Pedagogías sentipensantes y revolucionarias en la praxis educativo-política de los movimientos sociales de América Latina. Revista Colombiana de Educación, 1(80), 269-290.

Rocha-Buelvas, A. & Ruíz-Lurduy, R. (2018). Agendas de investigación indígena y decolonialidad. Izquierdas, 41, 184-197.

Savin-Baden, M. & Howell, C. (2010). New approaches to qualitative research: Wisdom and uncertainty. Routledge, Taylor & Francisc group.

Singh, J. (2018). Unthinking mastery: Dehumanism and decolonial entanglements. Duke University Press.

Tuhiwai, L. (2021). Decolonizing methodologies. Zed.

Universidad Autónoma del Caribe. (July 31st, 2020). El origen de la danza del Garabato explicada en el conversatorio ‘En línea con la tradición’ de la Universidad Autónoma del Caribe. https://www.uac.edu.co/el-origen-de-la-danza-del-garabato-explicada-en-el-conversatorio-en-linea-con-la-tradicion-de-la-universidad-autonoma-del-caribe/

Vasilachis, I. (2009). Los fundamentos ontológicos y epistemológicos de la investigación cualitativa. Forum Qualitative Social Research (FQSR), 10(2), 1-25.

Walsh. C. (2017). Entretejiendo lo pedagógico y lo decolonial: luchas, caminos y siembras de reflexión-acción para resistir, (re)existir y (re)vivir. Alter/nativas.

Webber, N. (2012). Subjective Elasticity, the “Zone of Nonbeing” and Fanon’s New Humanism in Black Skin, White Masks. Postcolonial Text, 7(4), 1-15.